Photos: Miikka Skaffari/WireImage; Marcus Ingram/Getty Images; Gary Miller/Getty Images; Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images; Patrick O'Brien Smith; Courtesy of the artist

list

6 Artists Expanding The Boundaries Of Hip-Hop In 2023: Lil Yachty, McKinley Dixon, Princess Nokia & More

Jazz, psychedelic rock, ambient and more permeate the work of artists such as Kassa Overall and Decuma. As hip-hop turns 50, meet the artists who are continuing to push the genre's multifarious sounds.

DJ Kool Herc was messing with soul vocals and drum breaks when he invented what’s now known as the break beat — the very element that gave birth to the genre on Aug. 11, 1973.

Hip-hop was literally built off a sample. And in the decades since, the genre has thrived off those same omnivorous instincts, oftentimes to where even the terms "rap" and "hip-hop" don’t feel precise enough to describe the genre’s innovation and sheer diversity. (Five years before [Kanye West](https://www.grammy.com/artists/kanye-west/6900) [declared rap the new rock ‘n’ roll](https://www.youtube.com/shorts/59vqspjDhaU) to describe its popularity, Los Angeles rapper Open Mike Eagle [wasn’t even satisfied](https://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/music/open-mike-eagle-on-indie-raps-breakthrough-year-6613867) with the word "indie" being tacked on to his brand of hip-hop: "That's too blanket of a term I think to really apply to what I attempt to do.")

As hip-hop turns 50, the artists behind some of its most exciting releases show that more than ever, the genre’s boundaries are porous — and that pushing boundaries remains in its DNA.

Decuma

"I can’t claim to be super methodical with my genre blending. … My emotions just well up in me and spill out in whatever form my brain decides," Decuma once said. The rapper and producer was being modest.

2023’s *[let's play pretend](https://decuma.bandcamp.com/album/lets-play-pretend)* offers the best possible explanation for his blend of hip-hop, ambient, and experimental genres, as if inspired by Xiu Xiu’s white-knuckle intensity: "I write ambient music because life feels like one long, dissonant drone," he raps in fourth track "basketball."

This genre-blending is how Decuma expresses, with admirable precision, the trauma that stems from physical, sexual and racial violence. It also underscores lyrics like, "I'm so alone with my secrets, and so I shared them with this f— stuffed tiger just so something can hear it." How it felt to be robbed of his innocence could not be made more explicit.

In September, Decuma will release a new album, titled *feeding the world serpent*.

Jamee Cornelia

On her 2023 album *art school dropout*, Jamee Cornelia created a relatable, modern-day soundtrack to the gig economy lifestyle. On "Campus Radio," Cornelia briefly pretends that she is a college radio disc jockey. Using her best late-night FM voice, she teases an interview with her school’s most promising musician, on "what it’s like to be a full-time student, a minimum wage cashier, and a touring musician."

Instead of just using her words, though, Cornelia uses her diverse artistic background — like when she was a videographer for her skate team, until ["Odd Future happened and all my friends became rappers"](http://voyageatl.com/interview/conversations-inspiring-jamee-cornelia/) — to depict what juggling those multiple hustles feels like. Sometimes, working the gig economy can feel like "Routine," where writing to-do lists for the week and month comes together as easily as her flow fits in the pocket. Other times, it's as grueling and cathartic as "Rock!," where crunchy hard rock guitars meet Three 6 Mafia-style club chants.

In sound and substance, Cornelia deftly creates a world where any small job (or genre, really) feels necessary to take on.

Kassa Overall

This GRAMMY-nominated bandleader, drummer, producer and rapper has already talked about how jazz and rap offer a more complete history of Black music in America than they do separately. He’s also explained why introducing rap sensibilities to jazz music makes sense in this modern age.

"Somebody like [Louis Armstrong](https://www.grammy.com/artists/louis-armstrong/452) or [Dizzy Gillespie](https://www.grammy.com/artists/dizzy-gillespie/16741) — a third of them was Lil B and Danny Brown energy." That’s why it was fire," [he told GRAMMY.com in May](https://www.grammy.com/news/interview-with-kassa-overall-about-new-album-animals). But his latest, *Animals*, also shows how the relationship between jazz and rap can be mutually beneficial.

On "Ready to Ball," Kassa’s wry musings about the music industry ("I need a contract with a couple zips and a full fifth / just to tell the truth at the pulpit / that this is all just bulls—") is a grounding force, amid a searching piano and skipping percussion. Those few seconds feel instructive, showing how rap doesn’t always need to make tidy loops out of jazz’s improvisational nature, in order to thrive.

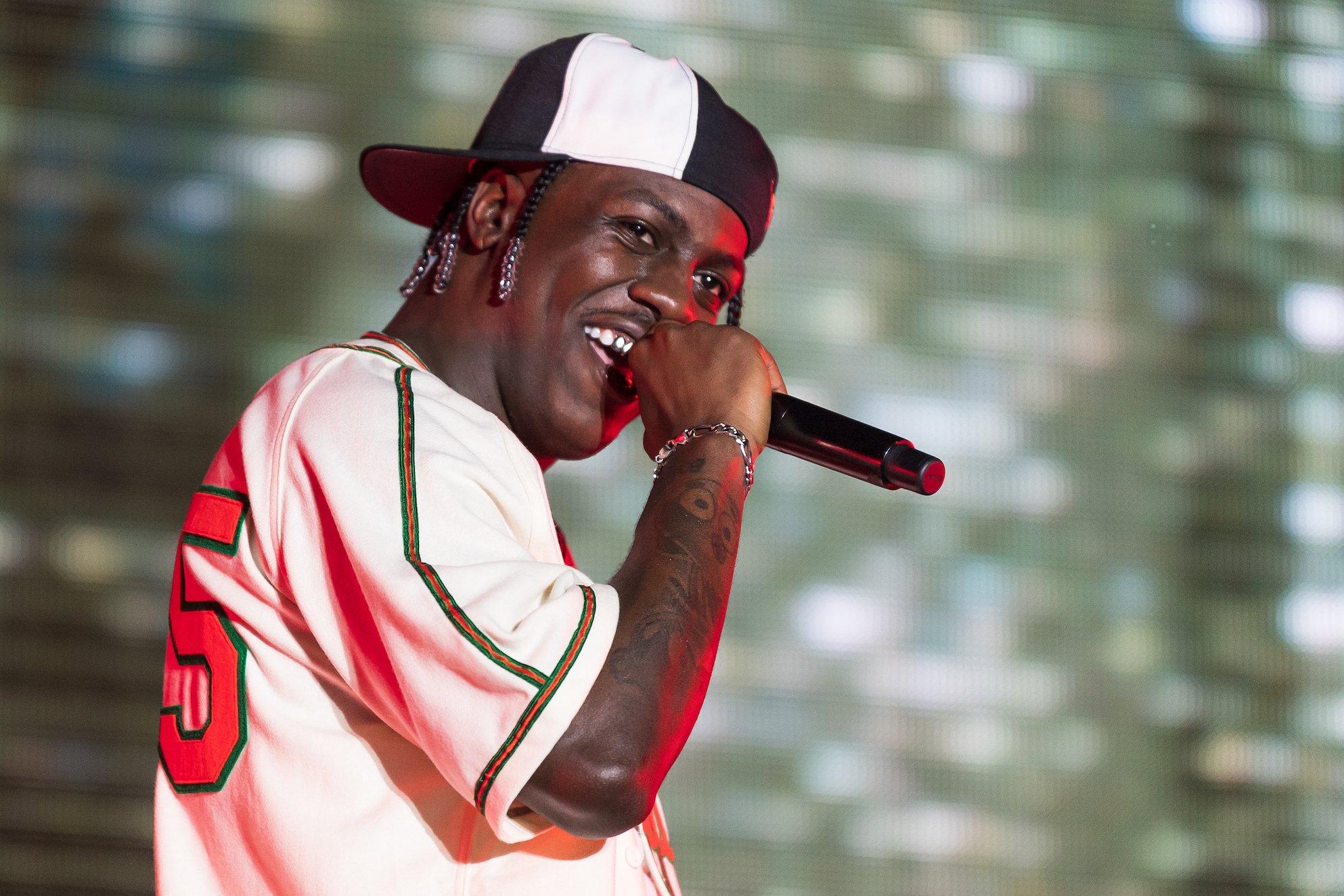

Lil Yachty

Prior to Let’s Start Here., two-time GRAMMY nominee Lil Yachty was already pushing hip-hop’s boundaries. While declaring himself the "King of Teens," the actual teen’s take on rap was initially irreverent, helping make the SoundCloud generation an easy target for classicists. It was only after his 2017 debut album, Teenage Emotions, that Yachty concerned himself with establishing goodwill within the genre — whether by mixtape-length tributes to Midwest hip-hop, or by writing and producing for City Girls, Drake and 21 Savage.

Yet according to Kevin "Coach K" Lee, co-founder of Lil Yachty’s label Quality Control, *Let’s Start Here.* is the album that Yachty has always wanted to make: A psychedelic rock coming-of-age journey, as inspired by [Pink Floyd](https://www.grammy.com/artists/pink-floyd/15905)’s *[Dark Side of the Moon](https://www.grammy.com/news/pink-floyd-the-dark-side-of-the-moon-50-anniversary-boxed-set-facts)*, and with help from Chairlift, Mac DeMarco, and Unknown Mortal Orchestra, among others. "He had been wanting to make this album from the first day we signed him. But you know — coming as a hip-hop artist, you have to play the game," Coach K told *[Billboard](https://www.billboard.com/music/features/lil-yachty-lets-start-here-interview-sxsw-billboard-cover-story-1235281282/).*

[Questlove](https://www.grammy.com/artists/questlove/11425) [said](https://www.instagram.com/p/Cn-LjwJu6MH/) that he needed 24 hours to process Yachty's "departure record." But the explanation [the Roots](https://www.grammy.com/artists/roots/7842) bandleader was looking for can be found in "WE SAW THE SUN!"’s outro, where Yachty [samples painter Bob Ross](https://www.xxlmag.com/lil-yachty-bob-ross-lets-start-here-album/). "Just let your imagination run wild," Ross says. "Let your heart be your guide."

McKinley Dixon

In the early 2010s, McKinley Dixon had to perform with a live band in order to get stage time. Otherwise, his sets would get cut short, because music venues figured that "rappers are not seen to be as interesting unless they have a band," Dixon says.

These days, though, incorporating live instrumentation and taking inspiration from other genres is a vital part of McKinley's creative process and how he adds gravitas to his storytelling: "My music is me watching *Death Note* with [Red Hot Chili Peppers](https://www.grammy.com/artists/red-hot-chili-peppers/16367) playing over it," [he told ](https://www.papermag.com/mckinley-dixon-interview-2659755035.html)*[PAPER](https://www.papermag.com/mckinley-dixon-interview-2659755035.html)*.

Meanwhile, in "Sun, I Rise," Dixon features a wandering harp ambling over the song’s lush jazz-rap arrangement. "OG slap the back of my head / said ‘Stop f—ing around / You only fall when you think you smarter than those / shooting you down.’" Dixon raps. This underscores the journey ahead in his new album *Beloved!, Paradise! Jazz!?*, an exploration of how Black boys come of age amid forces that implore them to grow up even faster.

Princess Nokia

Seven years ago, right as Princess Nokia was establishing herself as a hip-hop artist to watch, she had genre-bending visions for her artistry that even startled The Guardian’s head rock and pop critic Alexis Petridis. "I will happily be GG Allin of the hip-hop world," she said, referencing the biggest degenerate punk music has seen.

The music references in her latest, 2023’s *i love you but this is goodbye*, aren’t nearly as hell-raising. But, with how the album shifts from pop-punk ("closure") to jungle ("complicated") and cyberpop ("the fool") in its first three tracks alone, expanding hip-hop’s boundaries remains how Princess Nokia celebrates her autonomy. That’s not just as an artist this time, but as a maturing woman learning that a romantic relationship was never meant to complete her. Even ‘90s R&B-rap throwback "happy" gets that point across, with how her hook interpolates "Clint Eastwood" by Gorillaz: "I’m useless, but not for long / the future is coming on."

[Listen To GRAMMY.com's 50th Anniversary Of Hip-Hop Playlist: 50 Songs That Show The Genre's Evolution](https://www.grammy.com/news/50th-anniversary-of-hip-hop-playlist-listen-essential-releases-by-decade)

Photos: Gary Miller/Getty Images; ANGELA WEISS/AFP via Getty Images; Jason Mendez/Getty Images; Erika Goldring/FilmMagic; Joseph Okpako/WireImage

list

2023 In Review: 5 Trends That Defined Hip-Hop

While hip-hop’s lack of chart success was rife for discussion during the first half of the year, there was plenty of great rap music in 2023. It may not be reaching the top of the charts as frequently, but the genre is as vibrant as ever.

For the first half of 2023, hip-hop’s lack of chart success seemed to be all anyone could talk about.

No hip-hop album went No. 1 until Lil Uzi Vert’s Pink Tape in July, and it wasn’t until September that Doja Cat broke a 13-month dry spell for the genre on Billboard’s Hot 100 singles chart with "Paint the Town Red" (the single is nominated for Best Pop Vocal Performance at the 2024 GRAMMYs, alongside Miley Cyrus' "Flowers," "Vampire" by Olivia Rodrigo, Taylor Swift's "Antihero" and Billie Eilish's "What Was I Made For?").

This situation caused a bunch of hand-wringing. As hip-hop celebrated its 50th anniversary, was the genre past its prime — artistic, commercial or both? Was it, as one popular radio personality proclaimed, being eased out by mysterious powers-that-be in favor of Afrobeats or reggaeton?

While it may not be reaching the top of the charts as frequently as in years past, hip-hop is as vibrant as ever. As it turns out, there was plenty of great hip-hop around in 2023, thanks to both new and veteran artists. As hip-hop enters its next 50 years, look back on some of the trends that are keeping the genre one of the most innovative.

SoundCloud Rap Returns

"SoundCloud rap" was an appellation given to a group of artists starting sometime in the mid-2010s. It referred to artists like XXXTentacion, Trippie Redd, Smokepurpp, Lil Pump, Denzel Curry, and many more. Often the artists looked as colorful as the music sounded — face tattoos were the norm — and its approach was structurally experimental, emo-influenced, and raw. (A good summary of the movement is here).

SoundCloud rap as a movement ran out of steam in 2019 after a string of tragic deaths (Lil Peep, XXXTentacion, Juice WRLD). But now a new iteration of it is back.

Yeat, who in 2018 back at the tail of SoundCloud rap’s initial run was hailed as "SoundCloud’s latest sensation," has developed into a major star who duets with Drake on the latter's For All The Dogs. He and a crew of artists such as Ken Car$on, Midwxst, and SSGKobe are taking the high-energy vibe of the initial wave of SoundCloud rap artists like Playboi Carti, and updating it for a new generation.

This new slate is, as other coverage has pointed out, overall less chaotic and noisy, and more professional-sounding, than its predecessors, while still having similar youthful energy.

Women Are Leading The Way

For far too long in mainstream hip-hop, women have been relegated to "the one girl in the crew" status, or been pitted against each other by fans, media, and pretty much everyone else with a there-can-only-be-one mentality. Despite that, girls and women have always played a key role in the genre, both in front of the mic and behind the scenes.

Fortunately those retrograde notions are dead in 2023. A diverse array of female rappers are leading the way artistically and commercially. On the commercial side of the ledger, last year’s GRAMMY Best New Artist nominee Latto was the first rapper to score a No. 1 hit in 2023, while GloRilla, Coi Leray and Best New Artist nominee Ice Spice (who is nominated in the category alongside Gracie Abrams, Fred again.., Jelly Roll, Coco Jones, Noah Kahan, Victoria Monét, and the War And Treaty) have all had big chart wins.

Other female artists who are making big noise include Tierra Whack (who this publication pinpointed as someone "leading the next generation"), Rico Nasty, Flo Milli, Kash Doll, BIA, and countless others. For a primer on both how we got here and what the current generation is up to, make sure to watch the Netflix documentary Ladies First: A Story of Women in Hip-Hop.

Change Is Happening At The Margins

As with most art forms, the real excitement happens at the edges. Whether it's people who are operating outside of the commercial mainstream, or artists who are pushing to expand the idea of what being a rapper even means by incorporating other types of music, the margins are where all the fun is.

In 2023, artists continued to incorporate other genres to the point where questioning whether their music is still hip-hop becomes impossible to answer — see Lil Yachty’s recent psychedelic turn and Kassa Overall’s jazzy explorations. There are also the truly outré, experimental artists like Fatboi Sharif, whose dark and abstract vision is unlike anything else; and psychedelic deep thinker Gabe ‘Nandez.

And there is a vibrant, arty underground scene that has its own revered veterans like billy woods whose profile (both solo and as a member of the duo Armand Hammer with ELUCID) has been rising rapidly over the past few years; as well as a contingent of younger aligned musicians like Fly Anakin and Pink Siifu.

Veterans Are Killing The Stage

While some young artists are canceling or postponing live dates, or having tickets on the secondary market go for surprisingly low prices, there’s one contingent of artists who are having no problem filling seats and satisfying fans: the OGs.

The culture's legends crossed the country on stacked tours — many of which coincided with the much-heralded 50th anniversary of hip-hop.The Rock the Bells F.O.R.C.E. Tour featured LL Cool J, the Roots, and a busload of veteran rappers. 2023 also saw the Nas and Wu-Tang Clan New York State of Mind Tour, and 50 Cent’s Final Lap Tour.

Hip-hop’s longtime stars are tearing down stages all over the world, and filling up arenas while doing it. Despite a popular culture always focused on the new and next, these OGs are showing their staying power where it counts — onstage, in front of the people.

Hip-Hop Celebrates Its Golden Anniversary

Hip-hop officially celebrated 50 years of groundbreaking culture in August, but 2023 became a year-long celebration of the genre’s past. Figures going all the way back to Kool Herc and DJ Hollywood had huge moments and a renewed focus on their achievements.

The celebration wasn’t limited to one single Yankee Stadium concert or one media outlet. It was instead a long and well-needed look back that spanned live events, museum exhibits, documentaries, books, and more. The retrospective really kicked off in February, with a killer showcase of hip-hop history at the 2023 GRAMMYs. And it continues all the way through to December with the Recording Academy’s "A GRAMMY Salute to 50 Years of Hip-Hop" special.

Photo: Courtesy of Kassa Overall

video

ReImagined: Kassa Overall Transforms Snoop Dogg's "Drop It Like It's Hot" With Jazzy Improvisation

Contemporary jazz star Kassa Overall uses his genre-bending of hip-hop and jazz to offer a new perspective on Snoop Dogg's 2004 hit single with Pharrell, "Drop It Like It's Hot."

While Snoop Dogg and Pharrell boast a bevy of chart-toppers across their respective careers, both artists' first No. 1 can be traced back to 2003 thanks to one special single: "Drop It Like It's Hot." The track went on to receive two GRAMMY nominations, Best Rap Song and Best Rap Duo/Group Performance. By the end of the 2000s, Billboard declared it the most popular rap song of the decade.

In this episode of ReImagined, contemporary jazz artist and drummer Kassa Overall delivers a live performance of "Drop It Like It's Hot" from a highway. Overall uses pieces of the song's original iconic production — like its tongue clicks — but ultimately turns it into his own with jazzy improvisation.

Overall's spirited performance is a teaser for what fans can expect on his Ready to Ball World Tour, which kicked off with a sold-out performance in Tokyo on Oct. 19. The trek will see Overall hit 30 cities in the United States and Europe, ending on March 21 in Knoxville, Tennessee.

Press play on the video above to hear Kassa Overall's unique rendition of Snoop Dogg and Pharrell's "Drop It Like It's Hot," and check back to GRAMMY.com for more new episodes of ReImagined.

Photo: Jason Koerner/Getty Images

interview

Lil Yachty Wants You To Be "Ready For Everything" At The Field Trip Tour

As Lil Yachty hits the road for his 42-date global tour, the rapper details how he'll be bringing his trippy album 'Let's Start Here' to life — and why he feels like his seven-year career is only just getting started.

Fans first got to know Lil Yachty for his catchy, sing-songy tunes like "One Night" and "Minnesota," rap songs that sound like the rapper's once-signature red braids: bright and attention-getting. But as the man who once dubbed himself the "king of the teens" has now become a father in his (gasp!) mid-20s, his musical horizons have expanded.

While Lil Boat is still making catchy tracks (see his minute-and-a-half long earworm "Poland," released last fall), his latest album is something else entirely. Inspired by big statement LPs like Pink Floyd's 1973 classic Dark Side of the Moon, Lil Yachty's Let's Start Here is a psychedelic record created with members of Chairlift and MGMT, as well as Mac DeMarco, Alex G and a handful of other out-of-the-norm collaborators. While the style change may have been unexpected for many, it came out exactly as Yachty envisioned it.

"It felt future-forward, it felt different, it felt original, it felt fresh, it felt strong," he says. "I'm grateful for the response. It's nice to have people resonate with a body of work that you've worked so hard on and you care so deeply about."

Yachty's most recent release, a four-song single pack featuring the swirling "TESLA," brings him back to a more traditional hip-hop style — by Lil Boat standards, anyway. But even with the four new tracks sprinkled throughout the set list, he's still determined to share the sound and vibe of Let's Start Here with his listeners.

The Field Trip Tour, which Lil Yachty kicked off in Washington, D.C. on Sept. 21, brings the album's trippy vision to the stage. The rapper recruited an all-women band for his latest trek, which includes Lea Grace Swinson and Romana R. Saintil on vocals, Monica Carter on drums, Téja Veal on bass, Quenequia Graves on guitar, and Kennedy Avery Smith on keys.

"My life is surrounded by women," Yachty explains. "I feel like they are the most important aspect to this world and that they don't get enough credit or shine — especially Black women."

GRAMMY.com caught up with Yachty as he was on his way to rehearsal to chat about the tour, the album, and what he learned from four old British guys.

You made your band auditions public by announcing them on social media, which is not the usual way of going about these things. When you had the auditions, what was it like? How many people showed up?

Hundreds of women came from all over. People sent in auditions online. It was so fun to hear so much music and see talent and meet so many different personalities. I felt like Simon Cowell.

Other than musical ability, what were you looking for?

It was nothing more than talent. There would be multiple people with extreme talent, so then it became your own creative spunk: what did you do that made me say, "Oh, okay. I like this. I like this"? I wanted a badass group.

What was behind the decision to put the call out for women only?

My life is surrounded by women — my two assistants, my mother as a manager, a lot of my friends are women. Women really help me throughout my day.

I just think that women are so powerful. I feel like they rule the world. They are the most important aspect to this world and they don't get enough credit or shine, especially black women. So that was my aura behind it. I just wanted to showcase that women can shred just as good as men.

Is the band going to be performing on your older rap material as well, in addition to the album cuts?

No. I'm not a big fan of rendition rap songs. I think the feeling is in the beat, the feeling is in the instrumentation. When you have to reconstruct it, the bounce gets lost a bit.

Tell me about the rehearsal process once you selected the band members. What was that like?

They're all so talented, so they all learned it very quick. I gave [the music] to them early, and gave them the stems. When it was day one, they all knew the songs. Even my new guitarist that came in later than everyone, she came in knowing the music.

The rehearsal project for this tour was a little different, because I'm reconstructing the whole album. I'm moving everything around and changing all the transitions and trying to make it trippy. So it's a process of me figuring out how I want to do things. But they're so talented and so smart, all I have to do is tell them what I want, and they'll do it instantly.

Like yesterday, I wanted a solo on the end of a song called "The Alchemist." Because at the end of [the album version] is this [singer Brittany] Fousheé breakdown and she's singing in a falsetto. But I took her vocals off and I wanted a solo. And [a band member] was working through it yesterday and it wasn't quite there. But I'm on the way to rehearsal now, and I know when I walk in this room, it'll be done. It'll be crazy. So they all take it very serious and they care, and I love them so much.

The festival shows you've done so far have had everyone in Bantu knot hairstyles, sometimes with face paint. Is that going to be the look for this tour?

No, I don't think so.

What was the thinking behind that look?

I was getting really deep into the world of '70s bands, '60s bands. Just unison: moving as one, looking like one, feeling like one. A family, a group, a team. You see us, we're all together.

When you play rap shows, so much of what you're doing is keeping a high-energy mood—getting the crowd going, starting mosh pits. With the new songs, it's about a diversity of feelings. What was that like for you as a band leader?

I'll tell you, it was not easy. I've been in this industry for seven years, and my shows have been high-energy for seven years. So the first time I went on a stage and performed Let's Start Here, I felt like, "Oh wow, they hate me. Do they hate this?" Plus I have in-ears, so I can't hear the crowd cheering. I don't perform with in-ears when I do rap shows.

It took me some time to get used to the switch. Tyler, the Creator once had a talk with me and explained to me that, it's not that they don't f— with you, it's that they're taking it in. They're comprehending you. They're processing and enjoying it. That clicked in me and I got a better understanding of what's going on.

What is it like in the same show to go from the Let's Start Here material to the rap stuff?

It's a relief, because that's going to my world. It's super easy for me. It's like flipping the switch and taking it to the moon.

Now that it's been the better part of a year since Let's Start Here came out, how are you feeling about it? What sense do you have of the reaction to it?

Since before it came out, when I was making it, I always felt so strongly because it was something that I felt inside. It felt future-forward, it felt different, it felt original, it felt fresh, it felt strong.

I'm grateful for the response. It's nice. It's not what you do it for, but it is extra credit. It's nice to get that love and to have people resonate with a body of work that you've worked so hard on and you care so deeply about.

Have you felt peoples' reactions change over the past few months?

Well, this is the first time when people are like, "Man, that album changed my life" or "It took me to a different place." People love my music — always have — but this reaction is, "Man, this album, man, it really took me there."

It did what it was supposed to do, which was transcend people. If you are on that side of the world and you're into that type of stuff, it did its job, its course — the same course as Dark Side of the Moon, which is to take you on a journey, an experience.

What was it about Dark Side that grabbed you?

Everything. The cover, the sounds, the transitions, the vocals, the lyrics, the age of Pink Floyd when they made it. I could go on. I got into deep fascination. It was so many things. It's just pure talent.

**I've read that you studied Pink Floyd quite a bit, watching interviews and documentaries. What were some of the things you learned from that process and brought to Let's Start Here?**

So many things. The most important element was that I wanted to create a body of work that felt cohesive and that transcended people, and that was a fun experience that could take you away from life.

I was curious about the song ":(failure:(," where you give a speech about failing. What were your inspirations for that?

"Facebook Story" by Frank Ocean, which is about a girl who thought he was cheating on her because he wouldn't accept her on Facebook. It inspired me to talk about something.

At first I wanted [":(failure:("] to be a poem, and I wanted my friend to say it. We tried it out, but his voice was so f—ing deep. And his poem was so dark — it was about death and s—. I was like, Damn, n—, lighten up. But then I was just like, you know what, I'll do it, and I'll speak about something very near and dear to me, which was failure. I felt like it would resonate with people more.

**The idea of time shows up on the album a lot, which is something it has in common with Dark Side of the Moon. You talk about running out of time. What are you running out of time to do?**

Sometimes I feel like I'm growing so fast and getting so old, and maturing and evolving so quickly, and so many opportunities come into my life. You go on tour, and then you start working on an album, and you run out of time to do certain things. It's like, "Are we going to be together? If not, I have other things to do."

I think that's where it comes from. I don't have all day to play around. Too many things to do. Then it transpires to feel like I'm running out of time.

I love "drive ME crazy!" I was wondering if there are any particular male/female duets that you looked at as a model when designing that song.

Fleetwood Mac. Again, with all the inspirations for these songs, I still did my twist on them. So I don't want people to go and be like, "Oh, that sounds nothing like a Fleetwood Mac song." I wasn't trying to copy a Fleetwood Mac song. It just inspired me to make a song in that feeling, in that world.

When you began your career, you were the "king of the teens." Now you're a father in your mid-twenties. Who's your audience these days? Is it the people who were teens when you started your career, who are now in their 20s like you, or is it a new crop of teenagers?

I think now it's from the 12-year-olds to the 40-year-olds. My last festival, I had 50-year-olds in my show. That was so amazing. In the front row, there was an 11-year-old asking for my sneakers, and then in the back, it was 50- and 60-year-olds. It was crazy. The age demographic is insane.

Whenever I'm leaving somewhere, I like to have the window down and see people. [At my last festival] these 60-year-olds were leaving. They're like, "Man, your album, we love it. That show was so great." And that's awesome, because I love [that my music can] touch everyone.

You've been opening your recent shows with "the BLACK seminole." What does that phrase mean to you? How does it relate to the sound of the song and the rest of the lyrics?

It's saying, "I'm a warrior, I am a king, I am a sex symbol, I am everything good and bad with man, and I'm Black, unapologetically." That's what it's about.

Any final thoughts about the tour?

Just that it's an experience. You're not walking into a rinky-dink [show with] some DJ. This is going to be a show.

I feel like it's the start of my career. I just want people to come in with an open mindset. Not expecting anything, ready for everything.

10 Bingeworthy Hip-Hop Podcasts: From "Caresha Please" To "Trapital"

Photo: Al Pereira/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

10 Albums That Showcase The Deep Connection Between Hip-Hop And Jazz: De La Soul, A Tribe Called Quest, Kendrick Lamar & More

Hip-hop and jazz are two branches of Black American music; their essences have always swirled together. Here are 10 albums that prove this.

Kassa Overall is tired of talking about the connections between jazz and rap. He had to do it when he released his last two albums, and he has to do it again regarding his latest one.

"They go together naturally," he once said. "They're from the same tree as far as where they come from, which is Black music in America. You don't have to over-mix them. It goes together already."

Expand this outward, and it applies to all Black American musics; it's not a stretch to connect gospel and blues, nor soul and R&B. Accordingly, jazz and rap contain much of the same DNA — from their rhythmic complexity to its improvisational component to its emphasis on the performer's personality.

Whether in sampling, the rhythmic backbone, or any number of other facets, jazz and rap have always been simpatico; just watch this video of the ‘40s and ‘50s vocal group the Jubilaries, which is billed as the “first rap song” and is currently circling TikTok. And as Overall points out to GRAMMY.com, even jazz greats like Louis Armstrong or Dizzy Gillespie had “Lil B and Danny Brown energy.”

From A Tribe Called Quest to the Roots to Kendrick Lamar, rap history is rife with classics that intertwine the languages of two Black American artforms. Here are 10 of them.

De La Soul — 3 Feet High and Rising (1989)

GRAMMY-winning Long Island legends De La Soul's catalog is finally on streaming; now's the perfect time to revisit these pivotal jazz-rap intersecters.

Featuring samples by everyone from Johnny Cash to Hall and Oates to the Turtles, their playful, iridescent, psychedelic 1989 debut, 3 Feet High and Rising, is the perfect portal to who Robert Christgau called "radically unlike any rap you or anybody else has ever heard,"

3 Feet High and Rising consistently ranks on lists of the greatest hip-hop albums of all time. In 2010, the Library of Congress added it to the National Recording Registry.

A Tribe Called Quest — The Low End Theory (1991)

If one were to itemize the most prodigious jazz-rap acts, four-time GRAMMY nominees A Tribe Called Quest belong near the top of the list. Their unforgettable tunes; intricate, genre-blending approach; and Afrocentric POV, put them at the forefront of jazz-rap.

There are several worthy gateways to the legendary discography of Q-Tip, Phife Dawg, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, and Jarobi White,, like 1993's Midnight Marauders and 1996's Beats, Rhymes and Life.

But their 1991 album The Low End Theory, was a consolidation and a watershed. From "Buggin' Out" to "Check the "Rhime" to "Scenario" — featuring Busta Rhymes, Charlie Brown and Dinco D — The Low End Theory contains the essence of Tribe’s vibrant, inventive personality.

Plus, it's not for nothing that they enlisted three-time GRAMMY winner Ron Carter to play on The Low End Theory; he's the most recorded jazz bassist in history.

Dream Warriors — And Now the Legacy Begins (1991)

Representing Canada are Dream Warriors, whose And Now the Legacy Begins was a landmark for alternative hip-hop.

King Lou and Capital Q's 1991 debut eschewed tough-guy posturing in favor of potent imagination and playful wit. Christgau nailed it once again with his characterization: "West Indian daisy age from boogie-down Toronto."

Its single "My Definition of a Boombastic Jazz Style" samples "Soul Bossa Nova" by 28-time GRAMMY winner Quincy Jones — who, among all the other components of his legacy, is one of jazz's finest arrangers. The tune would go on to become the Austin Powers theme song; in that regard, too, Dream Warriors were ahead of their time.

The Pharcyde — Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde (1992)

All of Black American music was fair game to producer J-Swift; on the Pharcyde's classic debut Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde, he sampled jazzers like Donald Byrd and Roy Ayers alongside Marvin Gaye, Jimi Hendrix, Sly and the Family Stone, and more. Over these beds of music, Fatlip, SlimKid 3, Imani, and Bootie Brown spit comedic bars with blue humor aplenty.

"I'm so slick that they need to call me, "Grease"/ 'Cause I slips and I slides When I rides on the beast" Imani raps in "Oh S—," in a representative moment. "Imani and your mom, sittin' in a tree/ K-I-S-S (I-N-G)."

All in all, the madcap, infectious Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde is a pivotal entry in the jazz-rap pantheon. One reviewer put it best: "[It] reaffirms every positive stereotype you've ever heard about hip-hop while simultaneously exploding every negative myth."

Digable Planets — Reachin' (A New Refutation of Time and Space) (1993)

Digable Planets' Ishmael Butler once chalked up the prevalent jazz samples on their debut as such: "I just went and got the records that I had around me," he said. "And a lot of those were my dad's s—. which was lots of jazz." It fits Digable Planets like a glove.

"Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat)" contains multiple elements of Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers' "Stretching"; "Escapism (Gettin' Free" incorporates the hook from Herbie Hancock's "Watermelon Man"; and "It's Good to Be Here" samples Grant Green's "Samba de Orpheus. Throughout Reachin', Butler, Craig Irving and Mary Ann Viera proselytize Black liberation in a multiplicity of forms.

Pitchfork nailed it when it declared, "Reachin' is an album about freedom — from convention, from oppression, from the limits imposed by the space-time continuum."

Gang Starr — Daily Operation (1992)

In the realm of Gang Starr, spiritual consciousness and street poetry coalesce. Given that jazz trucks in both concepts, it's a natural ingredient for DJ Premier and Guru's finest work.

One of their first masterpieces, Daily Operation, contains some of jazz's greatest minds within its grooves. "The Place Where We Dwell" samples the Cannonball Adderley Quintet's "Fun"; Charles Mingus' "II B.S" is on "I'm the Man"; the late piano magician Ahmad Jamal's "Ghetto Child" pops up on "The Illest Brother."

Throughout their career, DJ Premier and Guru only honed their relaxed chemistry; jazz elements help give their music a natural swing and sway. (Their musical partnership continues to this day; Gang Starr is releasing music this very week.)

The Roots — Things Fall Apart (1999)

Three-time GRAMMY winners The Roots' genius blend of live instrumentation and conscious bars launched them far past any "jazz-rap" conversation and into mainstream culture, via their role as the house band on "The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon."

Elements of limbic, angular jazz can be found throughout their discography, but their major label debut Do You Want More?!!!??! might be the most effective entryway into their blend of jazz and rap. ("Silent Treatment" features a bona fide jazz singer as a guest, Cassandra Wilson.)

Whether it’s the burbling "Distortion to Static," or the jazz-fusion-y "I Remain Calm," or the knockabout "Essaywhuman?!!!??!", venture forth into the Roots' discography; they're a hub of so many spokes of Black American music.

Madlib — Shades of Blue (2003)

As jazz-rap connections go, Madlib's Shades of Blue is one of the most pointed and direct.

Therein, he raids the Blue Note Records vault and remixes luminaries from Wayne Shorter ("Footprints") to Bobby Hutcherson ("Montara") to Ronnie Foster ("Mystic Brew," flipped into "Mystic Bounce"). In the medley "Peace/Dolphin Dance," Horace Silver and Herbie Hencock's titular works meet in the ether.

Elsewhere, Shades of Blue offers new interpretations of Blue Note classics by Madlib's fictional ensembles Yesterday's New Quintet, Morgan Adams Quartet Plus Two, Sound Direction, and the Joe McDuphrey Experience — all of whom are just Madlib playing every instrument.

In recent years, Blue Note has been hurtling forward with a slew of inspired new signings — some veterans, some newcomers. Through that lens, Shades of Blue provides a kaleidoscopic view of the storied jazz repository's past while paving the way for its future.

Kendrick Lamar — To Pimp a Butterfly (2015)

Lamar's game-changing third album featured a mighty cross-section of the most cutting-edge jazz musicians of its day, from Robert Glasper to Kamasi Washington.

While hip-hop has had a direct line to jazz for decades — as evidenced by previous entries on this list — Lamar solidified and codified it for the 21st century in this sequence of teeming, ambitious songs about Black culture, mental health and institutional racism.

"Kendrick reached a certain level with his rap that allowed him to move like a horn player," Overall told Tidal in 2020. And regarding Lamar’s present and future jazz-rap comminglings, Overall adds, "He opened up the floodgates of creative possibilities."

Kassa Overall — Animals (2023)

The pieces of Overall's brilliance have been there from the beginning, but never had he combined them to more thrilling effect than on Animals — where jazz musicians like pianists Kris Davis and Vijay Iyer commingle with rappers like Danny Brown and Lil B.

"I would rather people hear my music and not think it's a jazz-rap collage," Overall once told GRAMMY.com. "What if you don't relate it to anything else? What does it sound like to you?"

When it comes to the gonzo Danny Brown and Wiki collaboration "Clock Ticking," the Theo Croker-assisted "The Lava is Calm," and the inspired meltdown of "Going Up," featuring Lil B, Shabazz Palaces and Francis & the Lights — this music sounds like nothing else.

Over the decades, Black American musicians have swirled together jazz and rap into a cyclone of innovation, heart and brilliance — and there’s seemingly no limit to the iterations it can take on.

Kassa Overall Breaks The Mold And Embraces Absurdity On New Album Animals